The next frontier

Scientia ad initium novum

As I noted in my brief inaugural post here at The Progress Bar, there are lots of reasons I’m excited about 2026. A big one is that I anticipate having more time to read, think, and write about what it takes to produce a scientific breakthrough. It’s somewhat surprising to me that so many practicing scientists, who are devoted to using data to unravel the mysteries of life and the universe, seem to have consigned this question to the realm of the unmeasurable. That might once have been true, but recent advances in data science and computational power have changed the game.

If you’re here, it’s safe to say you too are curious about measuring and predicting scientific progress. Having the opportunity to share my thoughts with you is another reason I’m looking forward to the coming year. Before we get started in earnest, though, it seems like a good idea to tell you a little about my philosophy, my approach to this problem, and why I think now is the time to tackle it.

First, the philosophy. Science is the practice of making reproducible observations about a defined system, with the intent to use those observations to formulate testable predictions. That first part – making reproducible observations – is about describing your system. This is an important and necessary prerequisite to predicting its behavior, but if a field gets stuck here, it is not doing effective science. Neither is a field doing effective science if its observations don’t reproduce, or if it requires practitioners to continually violate Occam’s razor by cutting their system into smaller and smaller pieces to preserve the dominant paradigm.

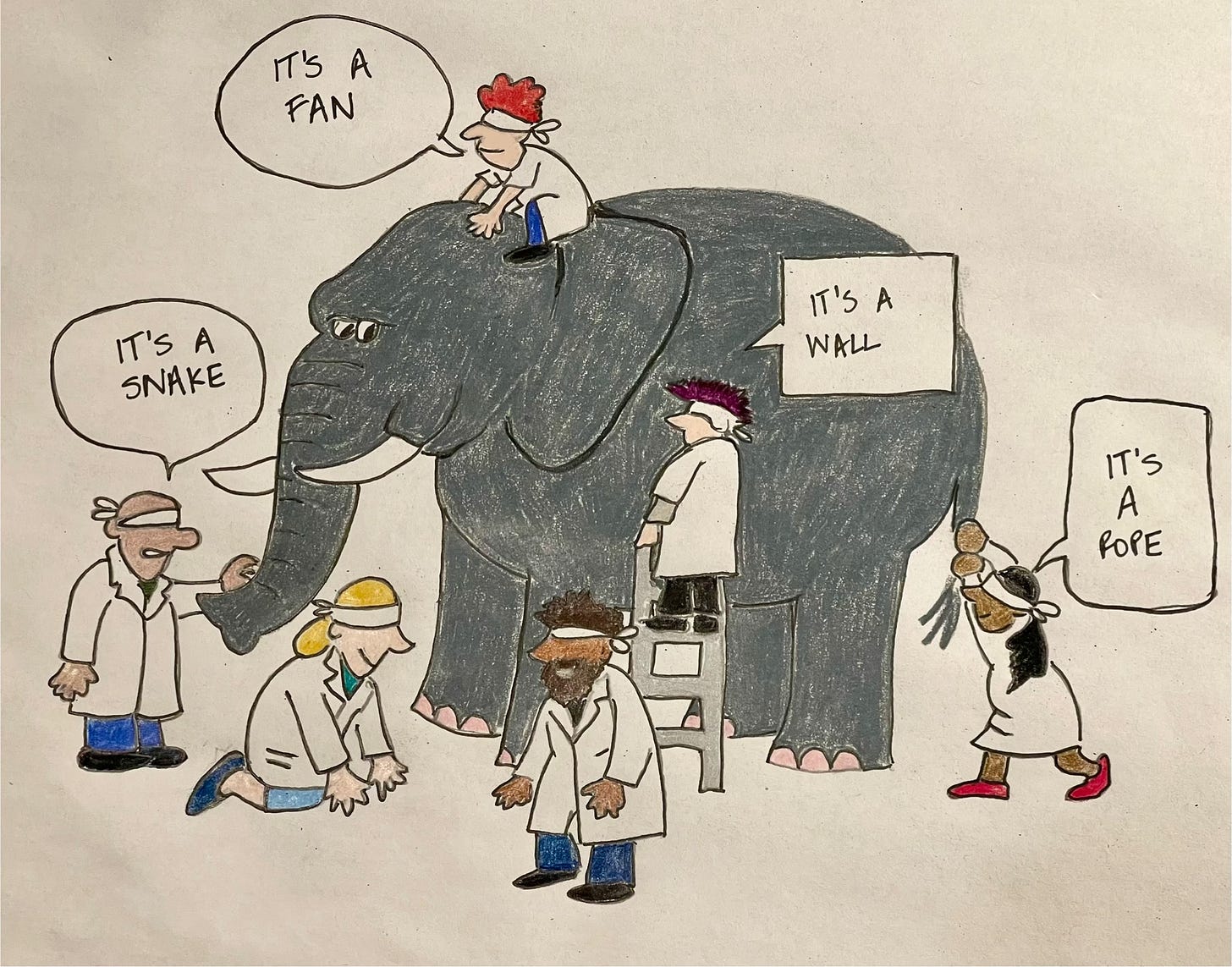

Assuming you’re describing a system for the first time (or you’ve chucked all your previous attempts and are starting fresh), there are arguably two ways to go about it – reductionism, or holism. The reductionist approach has a lot of attractions: isolate one factor, control the conditions, characterize it down to the atom. When done well, this can provide truly useful information, as in the case of structural biology. Of course, there are also limitations: the temptation to concentrate on facets of the problem that are easy to measure but functionally unimportant can be strong. Worse, like blindfolded scientists studying an elephant, focusing on just one part of the whole can lead to some dramatic mischaracterizations.

The alternative is to take a holistic approach: rather than concentrating on a leg, consider the entire animal. For better or worse, this is my preference, because it beautifully accommodates the starting premise that as humans, we are all somewhat stupid. We may not know the full list of parts that make up the whole we’re studying, and we certainly don’t know which are the important ones. If we’re clever about the questions we ask, nature will tell us what matters, although it may take us a while to understand the answer.

To fully realize their promise, then, this is my definition of what studies of scientific progress should be – rigorous, predictive, interrogating relationships rather than parts.

The major challenge for holistic approaches is that they require capturing, storing, and analyzing enough high-dimensional data to accurately represent reality. If this is the roadblock, our current opportunity is obvious. When Vannevar Bush wrote Science, the Endless Frontier in 1945, ENIAC filled a room. In 1964, when the Institute for Scientific Information published the first Science Citation Index, the world’s fastest supercomputer, the CDC6600, weighed close to six tons and had a top speed of three megaFLOPS. Today, a run-of-the-mill Dell desktop workstation is over 100,000 times faster, and at a compact 17” x 8.5” x 21”, only slightly larger than a carry-on roller bag.

Access to data sources has improved, too. Records of NIH and NSF awards have moved online. A majority of scholarly literature is now digital-first, with metadata that is structured and machine-readable; optical character recognition (OCR) does the heavy lifting of filling in much of the historical record. CrossRef, Unpaywall, and the Open Citation Collection have brought the primary currency of academic credit into the public domain [1]. Natural language processing can extract central semantic themes from a corpus of documents far too large for any one human to read in its entirety.

The idea to put these pieces together has been in the air for a while now. Writing for Science in 2017, Aaron Clauset, Daniel Larremore, and Roberta Sinatra identified a widespread belief that computational methods could predict incipient advances more objectively and accurately than expert opinion [2]. They also very shrewdly described many of the challenges associated with attempts at prediction, including the risk that poorly designed efforts could actually increase inequality, penalize novelty, and inhibit innovation. Four years later, James Weis and Joseph Jacobson shared an effort to predict impactful research in biotechnology, using a random forest classifier to sort through a subset of papers pre-selected by human subject matter experts for their likely impact [3]. Much of the discussion at the time, correctly in my opinion, centered on the potential for this approach to reinforce the Matthew Effect; grounding a model on legacy metrics like journal impact factor and h-index is convenient, but the new construct unavoidably inherits the known biases of the old components. It is true, though, that you have to start somewhere, and early efforts are often flawed.

Last month, my colleagues and I released a new paper predicting breakthroughs across all domains of biomedicine [4]. Our network-based approach relies exclusively on article-level assessment; we didn’t pre-judge which work might have value based on journal of publication or author history. Surveying past breakthroughs in fields as diverse as biophysics, genetics, cell biology, and clinical care, we found four common features that together act as the signal of an impending breakthrough, detectable more than five years, on average, in advance of the subsequent publication(s) that announce the discovery. Since science should make testable predictions, we screened papers published between 2014-2017 for our signal of likely future breakthroughs. Early returns look promising; one of our picks has already won a Lasker award.

I’m eager to see how our predictions continue to play out over the next few years. The work also opens lots of new questions I find interesting. For example, the time between the signal of an upcoming breakthrough and the breakthrough itself is variable; is that influenced by the number of researchers focused on the problem, by the availability of grant funding, or both? Or maybe neither? Our data also suggest that breakthroughs are more likely to occur when fields converge or diverge; does the density of ideas adjacent to an area of research influence its breakthrough potential? Answering these and other questions about how discoveries are made will help us create the conditions that promote them, and now is the time to do it.

Thank you to everyone who has already subscribed to this new venture; if this is your first visit, I hope you’ll sign up for more.

References

[1] B.I. Hutchins, K. L. Baker, M. T. Davis, M. A. Diwersy, E. Haque, R. M. Harriman, T. A. Hoppe, S. A. Leicht, P. Meyer, and G. M. Santangelo. The NIH Open Citation Collection: A public access, broad coverage resource. PLoS Biology, doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000385 (2019).

[2] A. Clauset, D. B. Larremore, and R. Sinatra. Data-driven predictions in the science of science. Science, 355:477-480 (2017).

[3] J. W. Weis and J. M. Jacobson, Learning on knowledge graph dynamics provides an early warning of impactful research. Nature Biotechnology, 39:1300-1307 (2021).

[4] M. T. Davis, B. L. Busse, S. Arabi, P. Meyer, T. A. Hoppe, R. A. Meseroll, B. I. Hutchins, K. A. Willis, and G. M. Santangelo. Prediction of transformative breakthroughs in biomedical research. bioRxiv, doi:https://doi.org/10.64898/2025.12.16.694385 (2025)